Circularity : Dilemmas of CALCulating Circularity in Cities

The ISWA CALC project awakened from its winter sleep with a hybrid mini-conference in Mechelen, Flanders, hosted by the OVAM, the Flemish Waste Management Organisation. This short article reviews the presentations and insights, and also reflects on what it’s like to hold hybrid conferences in a post-Covid Europe.

The CALC project: the challenge is to measure circularity, not (just) to talk about it

The Circular and Low Carbon Cities (CALC) project had its scoping meeting in 2019 and the project started in early 2020 with the support of the NVRD, the Dutch public cleaning association, as part of its contribution to the hosting agreement for the ISWA General Secretariat. The ambition of the project is to contribute practical metrics for cities (companies, institutions, individuals) for measuring circularity – and specifically waste prevention cascades – in practice and in real time.

"The ambition is partly a response to the observation that most circularity and circular economy initiatives are about intentions, or, if they are about actions, they are pointing to actions in terms of design and production,” says Anne Scheinberg, project leader of the ISWA CALC project. "Design and production are processes that result from decisions that cities have little ability to control or influence."

Design and production are processes that result from decisions that cities have little ability to control or influence.Anne Scheinberg, project leader of the ISWA CALC project

The project has been designed, to a certain extent, to answer the question: “What can we as the global solid waste sector – ISWA’s core constituency – do in practice to contribute to circularity?” For this reason, the project’s focus is on circularity after the point of first use, that is, when the product or material has entered the city, been used (or not), and could be disposed of into the city’s waste system. The result has been a slow but deliberate exploration of the most important cascades, that is, processes that maintain products and materials in ‘loops’ within the city, in some way extending their useful life and slowing their movement from use to disposal.

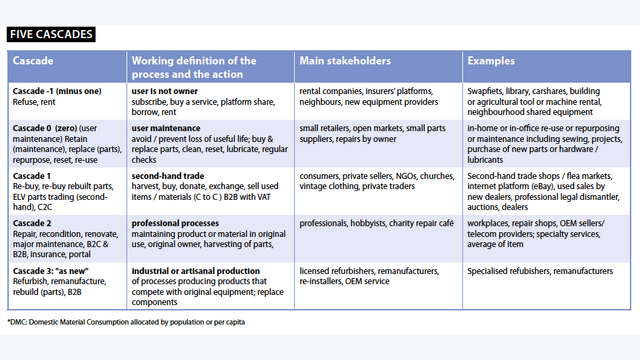

The project has been working to elaborate three indicators of circularity in cities. The first CALC indicator is the availability of circular processes – that is, options for cascading instead of or prior to becoming ‘waste’. The availability indicator defines availability as the number of addresses or waste prevention premises or processes which can be found in a city for each of the five focus cascades, as shown in Figure 1.

The second CALC indicator measures the intensity of use of the circular processes that are present in material flows in the designated cascades. In the original concept, it was possible for a city to choose whether to work this out as tonnes of materials or numbers of devices or units returned to the economy by passing through one or more cascades, but this could also be measured in terms of the numbers of people working in the cascades or total income to the processes. However, the recommendation is to use either tonnes or numbers of units.

The third CALC indicator is CO2 offsets from waste prevention in the city, in terms of avoided extraction and production impacts attributable to the extension or maintenance of useful life, and avoidance of disposal. This requires a set of more complex calculations, including knowing the energy and material footprint of the cascade processes, as well as the standard length of life of a particular product or material. At the present time, all three of these indicators have been tested

Working on Metrics for Circularity

Ironically, one of the biggest challenges for the project is the enormous attention paid to the circular economy. Most cities and many experts seem to refer to and understand the circular economy as the contributions that the private sector can make to ensure their products and packages are more recyclable.

In the CALC project we are looking beyond and ‘above’ recycling to how cities, countries and institutions can work on becoming more circular, and what kind of indicators would measure that.Anne Scheinberg

Among the options to stimulate and support the largely private operations ranging from the shoemaker to the mobile phone refurbisher, CALC has supported its members to engage in a number of activities and a small amount of original research.

In its first two years, the project co-financed original research on repair and refurbishment cascades for rechargeable batteries, rental and recycling for paper and cardboard, and rental, maintenance and repair for bicycles. An EU-funded Interreg project, called ShareRepair, is doing this through Google mapping of repair shops for electronics and other products in Flanders and bordering regions, as well as by supporting repair knowledge and infrastructure. This repair network involves many volunteers and is functioning alongside formal legal requirements of the extended producer responsibility (EPR) system.

One of the main challenges – in Flanders too, despite its ambitious circularity goals – is what operators in cities and regions are legally permitted to do in order to redirect products (such as bicycles) to a waste prevention cascade before the owner discards them. Once they are discarded, the law – at least in Europe – requires them to be dismantled for destruction and recycling.

In all cascades, the challenge is how to define ‘normal useful life’ so that it is possible to measure the greenhouse gas (GHG) offsets associated with extending useful life. After the initial research has been done, next on the list are electronics, textiles and potentially food.

For the mini-conference in Flanders, the project issued a ‘Call for Indicators’ to contribute to the body of knowledge on ways of measuring circularity.

The aim was to provide examples on how cities measure today, and also to have a fruitful discussion about what cities need and want to better measure circularity and greenhouse gas offsets in their city.Gunilla Carlsson, chair of the Cities Network in the CALC project

The three most interesting contributions from the Call for Indicators were selected to give a presentation about their indicators and measurements. One presentation was about a negative indicator measuring failure to be circular, by analysing the existing waste stream for items that should have been redirected to repair or reuse or even parts capture. There was also another interesting contribution about dilemmas, problems and barriers to circularity. Now the work continues on how to present this at the ISWA World Congress in Singapore in September.

In the closing discussion of the mini-conference, a number of ideas were put forward about what the project should offer to cities and others in the coming 18 months, to be profiled at the World Congresses in 2022 and 2023.

Three success factors for an international hybrid meeting in a post-Covid era

The meeting held was a three-day event in Mechelen, Belgium, where two of the days were hybrid and one day was filled with study visits. The hybrid meeting brought together participants from mostly European countries in the physical room and online participants from countries ranging from Australia to South America, with a total time difference of almost 15 hours.

The first success factor we noticed was the introduction and ‘meet-and-greet’ time that we had planned for both in-person and online participants. This has always been important in physical meetings, but in a post-Covid era with its hybrid meetings, it is more important than ever before. By starting off the meeting by letting everyone get to know each other and find out more about how others were participating, such as local times and whether they were sitting at home or in an office etc., we were also able to create the conditions for fruitful discussions during the meeting.

The second success factor of a hybrid meeting is the role of the chair. It is important that after a break, the chair always begins with a brief summary of what happened before and during the break – for everyone – and also that all participants are given the opportunity to voice their opinion during the meeting, even if they have not raised their hand or do not have their camera on.

The third success factor is to have technical professional equipment available and a good sound system! It is also very helpful if all participants who join a digital meeting know that everything said in the room is heard by everyone, and that all

participants can also join in with all discussions

There are still difficulties to be overcome with hybrid meetings, and learning takes time. However, we do believe that hybrid meetings are here to stay. Hybrid meetings will give ISWA the opportunity to be a truly global and international organisation in the future. In practice, all members can join all meetings from all time zones around the world. We are moving to a new way of working in the post-Covid era, and we were proud to be leading the way with our meeting.