How is India dealing with the ever growing waste generation? : Rags to Riches? The Urban Waste Management in India Saga

The world faces an immense challenge in the form of expanding waste, which has reached unsustainable levels, driven by rapid urbanisation, economic growth, and shifts in consumption and expenditure patterns. This problem has been magnified in India due to the growing population and rural-urban migration.

North and East India witnessed a massive refugee influx during the Partition in 1947 and again during the Indo-Pak War in 1971. Land was hurriedly made available for them to live in without proper infrastructure. Today, roads in these "colonies"—even though they are posh—are too narrow for large garbage trucks to drive on. Until very recently, carts pulled by hand or bicycles went around collecting garbage from homes or the streets.

In a countrywide initiative, on October 2 2014 – Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday, the ‘Swachh Bharat Mission’ (SBM) or Clean India Mission, was launched by the Government of India. With Prime Minister Narendra Modi leading the mission, it was split into urban and rural parts. In urban areas, the focus was on constructing individual, community and public toilets and scientific solid waste management (SWM).

SBM 2023 data says that urban areas in India, representing about 377 million people, generate 55.6 million metric tonnes (MMT) of municipal solid waste (MSW) each year. By end-2023 the country’s urban population is expected to hit 600 million and generate 165 million tonnes of solid waste, 5-6 per cent of which will be plastic. While the collection efficiency has improved significantly—about 70 per cent is collected countrywide—MSW recovery and end-disposal processes need to be strengthened. The waste generated by cities is projected to grow by 5 per cent annually until 2050 to reach 436 MMT per year by 2050.

Stay connected - subscribe to our newsletters!

Plastic: Main Culprit

The advent of plastics in India around the 1950s led to massive complications. The harmful, long-term effects of single-use plastics (SUPs) are well known – threatening marine and other wildlife, clogging rivers and drainage systems – especially during the monsoons, and water/soil pollution (including in landfills) as they are non-biodegradable, are among a few. Besides, India lacks an organised plastic waste management system, which results in widespread littering.

So, some states took matters into their own hands. In 1998, Sikkim became the first Indian state to ban disposable plastic bags and was also among the first to target SUP bottles. It being a hilly state with remote villages, garbage collection was already challenging.

In 2020-21, India generated nearly 3.5 million tonnes of plastic. However, its per capita consumption of plastic at 11 kg per year is still among the lowest in the world (the global average is 28 kg per year). The government banned 21 SUP items such as plates, cups, cutlery, straws, packaging film, and cigarette packets in 2022. But the share of plastic used for these banned SUPs is less than 2-3 per cent of the total plastic waste generated in India!

So plastics are still in rampant circulation across the country, particularly in the low-end section of the economy. "Though the central government issued the ban, the implementation lies with the respective state governments and their state pollution control boards," as per Ravi Agarwal, director of environmental NGO Toxics Link. "There seems to be a lack of an effective implementation strategy from the states to enforce the ban fully," he added.

Related article: Food waste in India: Prevention strategies and outcomes

Some recommendations include imposing penalties, finding cheaper alternatives to SUPs, better collection infrastructure, increasing the current recycling capacity of 1.56 million tonnes per year, etc. But experts warn it will not be an easy task given that of the 26,000 tonnes of plastic waste generated across India daily, more than 10,000 tonnes stay uncollected.

Landfills: Unsanitary Dumping Grounds

India being the most populous country in the world with one-sixth of the world's population, according to UN estimates (overtaking even China), didn’t help matters. This growth led to the need for more land for basic infrastructure and landfills for waste management. The latter are known to contribute significantly to global warming, as they produce methane, a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential over 21 times that of carbon dioxide. MSW landfills are considered the third-largest source of methane generated from human activities and facilitate fires, which worsen air quality.

The Deonar waste dumping ground, or landfill in the city of Mumbai, is India's oldest and largest dumping ground, set up in 1927. India's capital city, Delhi, has three major dumpsites, cumulatively covering an area of 200 acres, carrying almost 28 million tonnes of legacy waste. The Okhla dumpsite is about 62 acres, with 6 million tonnes of legacy waste. The Ghazipur landfill site has been in operation since 1984. It has become a primary environmental and public health concern due to its massive size, poor waste management practices, and adverse impacts on the local environment and community. So the Delhi government’s Finance Minister, Kailash Gahlot, declared an ambitious deadline in March 2023 for clearing all three dumpsites – Okhla by December 2023, Bhalswa by March 2024 and Ghazipur by December 2024.

The Dhapa landfill, a major unsegregated solid waste dumping ground in Kolkata since 1987, has been causing frequent fires and subsequent air quality deterioration in the city. It is set to be cleared by June 2024, a target strongly recommended by the National Green Tribunal (NGT). However, as of April 2023, only 20 per cent of the 4 million tonnes of legacy waste have been treated (biomining and bioremediation – the methods chosen by the NGT, which allows extraction of usable materials from the garbage).

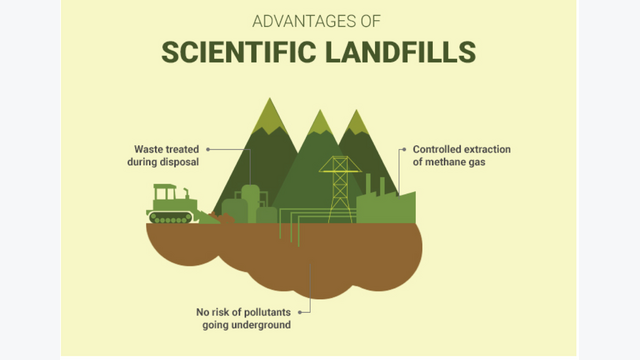

One solution proposed for India is using scientific landfills, where the waste is treated during disposal, and the methane generated is extracted in a controlled manner (see diagram below). This could also be waste-to-energy (WtE) plants that incinerate MSW to generate electricity.

Related article: Recycling in India: A market in transition

Scientific landfills might be a good solution for India's waste problem. Source.

Delhi has four WtE plants – one each at Ghazipur, Narela, Okhla and Tehkhand. Three of these were fined Rs. 500,000 each in August 2021 after the values of pollutants were found to exceed the permissible limits. The Delhi Pollution Control Committee recently launched public consultations for the proposed capacity upgrade at the Narela WtE plant, established in 2017, from 24 MW to 60 MW.

In the meantime, the Indian Biogas Association (IBA) has urged the Delhi government to set up biogas plants under a public-private-partnership (PPP) model at landfill sites in the national capital to deal with the mounting SWM problem.

Related article: Sugar mill waste-to-energy in India

Challenges Galore

- The informal sector — which includes waste-pickers, itinerant buyers, and small junk shop dealers — plays a significant role in waste management but remains largely unregulated. Ambikapur, a zero-landfill city, made women informal workers integral to its door-to-door waste collection and segregation systems by formalising them into a self-help group (SHG). MSW in the city is collected and further sorted into 156 categories, a first-of-its-kind initiative.

- Migrants from rural areas seeking work and a more modern lifestyle do not commit to their "adopted" living areas.

- With limited resources, most cities’ waste collection and transportation systems cannot keep up with the growing population and waste generation.

- The absence of adequate waste processing facilities has led to open dumping and burning of waste that contributes to air and land pollution, unmanaged landfills and environmental degradation.

- Citizens are not fully aware of the importance of waste segregation, recycling, and proper disposal, resulting in low participation rates and disregard for waste management rules.

Solutions to the Waste Problem

Local stakeholders – be it government agencies, local businesses, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), or citizen groups – need to take on more responsibility. They have a critical role in implementing and enforcing waste management policies on the ground and ensuring that waste is collected and disposed of properly. Through a residents' welfare association-led initiative, for example, Navjeevan Vihar, a 250-household colony in South Delhi, was among the first zero-waste wards in the capital. This has been made possible by prioritising segregating and encouraging residents to compost at source and minimise SUPs.

Promote small- and medium-scale initiatives, for example, to implement product reuse, recovery, and recycling (3R). The work done by Phool, a social enterprise that makes incense products from flower waste by integrating informal women workers, is an example of zero-waste and frugal innovation.

Sustainable Waste Management In Indore: A Case Study

Indore, a fast-growing city in the state of Madhya Pradesh in India, has emerged as a model for SWM practices. Over the past few years, it has consistently ranked as the cleanest city in India, thanks to the efficient waste management system put in place by the Indore Municipal Corporation (IMC). The city has over 3.2 million people and generates around 1,100 metric tonnes of waste daily. Prior to 2016, the city struggled with waste management, leading to unhygienic conditions, increased pollution, and negative impacts on public health.

However, the launch of SBM in 2014 led the IMC to undertake a comprehensive transformation of its waste management system. This involved an overhaul of existing infrastructure, policies, and community engagement initiatives, ranging from waste segregation at source and door-to-door collection to setting up a state-of-the-art waste processing facility capable of handling 1,000 metric tonnes of waste daily, including a 15 MW WtE plant and a 200 TPD (tonnes per day) composting plant.

The key, though, was the numerous awareness campaigns launched involving local celebrities, schools, and religious institutions to educate the public on the importance of waste segregation and cleanliness. Finally, regular and strict inspections, fines, and incentives were introduced to ensure compliance with waste management rules.

A key learning was that political will and administrative commitment are crucial for the successful implementation of waste management systems. The success of Swachh (Clean) Indore was primarily due to the collaboration of several stakeholders – NGOs, community associations, and citizen volunteers- who also took up the cause. CCTV cameras were installed for surveillance at the waste disposal site. An app (311) was launched to help with verification and service delivery/complaints. Walkie-talkies helped in directly connecting with the IMC official machinery. Linkages were created with the Department of Chemicals and Fertilizers for compost preparation and with the Department of Agriculture to ensure the supply of the compost to nearby farmers.

Small composting units were established to improve SWM at the source—at temples, schools, marriage venues, vegetable markets, gardens, parks, and the zoo. At one of the largest wholesale vegetable markets in Central India, Choitram Mandi (photo below), approximately 20-25 MT per day of fruit and vegetable waste is generated. IMC set up a bio-methanation plant (Bio-CNG) of 20 MTPD capacity to process all this waste. Approximately 800 kg of purified and compressed Bio-CNG with 95 per cent pure methane gas is generated daily and used as fuel in 15 city buses!

Another aspect that had to be considered was the rag pickers who were rendered jobless. With the help of NGOs, they have been trained and are now working at plastic waste collection centres. The plastic from these is sold to cement plants or used by the government for road construction.

As a result of all these efforts, over 90% of households in Indore now segregate their waste, significantly improving the efficiency of waste collection and processing and reducing the burden on landfills.

In conclusion, cities must learn from each other’s successes and failures for effective zero-waste implementation. While India still has a long way to go in becoming a zero-waste nation, current initiatives led by the government coupled with effective waste management at the local level point to a hopeful future.