How to minimize food waste : Food waste in India: Prevention strategies and outcomes

Introduction

According to the Asian Age, twenty-one million metric tonnes of wheat — almost equal to Australia’s production — rots each year in India due to improper storage. According to the Associated Chambers of Commerce, the country experiences a post-harvest loss of Rs 2 lakh crores (about 24 billion USD) annually due to lack of food processing units and storage facilities. The World Bank recently warned that 60 percent of the country’s food subsidies do not reach the poor; they are sponged by middlemen. The Food Corporation of India (FCI) was set up in 1964 to offer impetus to price support systems, encourage nationwide distribution and maintain a sufficient buffers of staples like wheat and rice but has been woefully inadequate to the needs of the country. Around one percent of GDP gets shaved off annually in the form of food waste. According to the agriculture ministry, Rs 50,000 crores (10 billion USD) worth of food produced is wasted every year in the country. One million tonnes of onions vanish on their way from farms to markets, as do 2.2 million tonnes of tomatoes. Tomatoes get squished if they are packed into jute sacks. Overall, five million eggs crack or go bad due to lack of cold storage. In resource terms, India is estimated to use more than 230 cubic kilometre of fresh water annually — enough to provide drinking water to 100 million people a year — for producing food items that are ultimately wasted. Besides this, nearly 300 million barrels of oil used in the process is also ultimately wasted. Wasting a kilogramme of wheat and rice would mean wasting 1,500 and 3,500 litres of water respectively that is consumed in their production.

Under such extreme data, food waste has started receiving much attention at the policy and management levels due to the strong research evidence identifying it not only in terms of wastage of valuable resources but also due to its environmental impact. There is considerable emerging evidence to suggest that land-filled food may be one of the major causes of landfill methane emissions. Climate change and its impact on food availability and access to a potentially ‘at risk’ population, has also drawn attention.

Defining Food Loss and Waste

Food loss is defined as “the decrease in quantity or quality of food”. Food waste is part of food loss and refers to discarding or alternative (non-food) use of food that is safe and nutritious for human consumption along the entire food supply chain, from primary production to end household consumer level. Food waste is recognized as a distinct part of food loss because the drivers that generate it and the solutions to it are different from those of food losses. (FAO, 2014)

So conceptually, FAO’s definition also covers

- Food loss refers to a decrease in mass (dry matter) or nutritional value (quality) of food that was originally intended for human consumption. These losses are mainly caused by inefficiencies in the food supply chains, such as poor infrastructure and logistics, lack of technology, insufficient skills, knowledge and management capacity of supply chain actors, and lack of access to markets. In addition, natural disasters play a role.

- Food waste refers to food appropriate for human consumption being discarded, whether or not it is kept beyond its expiry date or left to spoil. Often this is because food has spoiled but it can be for other reasons such as oversupply due to markets, or individual consumer shopping/eating habits.

- Food wastage refers to any food lost by deterioration or waste. Thus, the term “wastage” encompasses both food loss and food waste.” (FAO, 2013)

Reasons of food waste

Modernization

Industrialization of food systems, which results in a transition of food production and preparation from the home to the factory and from handcraft to purchasing, affects the foods that people consume, the types and quantities of food waste, and contributes to an increased physical distancing of people from food production and preparation. In areas with industrialized food systems with large amounts of food processing, people often purchase pre-made foods, or canned and frozen vegetables. As a result, pea pods and corn husks, for example, become industrial wastes, while packaging becomes more common in household waste. In industrialized food systems, consumers often purchase pre-cut meats, such as chicken legs, so there are no other components of the chicken to be disposed of as waste at the consumer level; the other parts of the chicken are utilized or disposed of by industry during the chicken processing.

Increased frequency of eating at restaurants and consumption of takeout food (commercially prepared but consumed at home), may contribute to increased food wastage as adults tend to be less likely to waste food that they prepared themselves or that a loved one prepared. In cultures based on handwork, handmade things are valuable as they embody many hours of labor. People who have not created or prepared something themselves, or watched a loved one do so, value labor less than those who have, and therefore, are more likely to throw it away.

Higher incomes are generally associated with the consumption of a more varied diet. There is a worldwide trend of increase in consumption of western diets comprising protein and energy-rich foods and convenience foods and a relative decrease in consumption of indigenous starchy food staples. Western diets with vulnerable short shelf-life foods are associated with greater food waste and greater drain on environmental resources. Increasing diversity in diet may also lead to increased wastage as opportunities to incorporate leftovers in the next or new meal are reduced. With consistent traditional meals, there are endless possibilities of such incorporation, minimizing leftover wastage.

Secondly, as incomes rise, people may be able to waste food more because food expenditures are no longer a major contributor to their total budgets.

Urbanization requires an extension of food supply systems, leading to diet diversification and disconnection from food production sources. People living in urban clusters have no sense of what their food is made of or how it was produced. Since food sources are removed from consumption, there are more opportunities to market diverse foods, not grown locally. Several studies have found residual waste from urban households has significantly more food components than rural households.

Food production and consumption patterns have shifted from local to regional to global, in terms of quantity, type, cost, variety, and desirability. Food tends to travel more over longer distances than earlier and consumers tend to consume more non-local food.

Food production and consumption patterns have shifted from local to regional to global, in terms of quantity, type, cost, variety and desirability.

Cultural factors

Culture plays a fundamental role in shaping food behaviors, nutrition and consequent waste generation. Countries like the US and Australia have few food traditions of their own and connections with long-standing food traditions and rituals is weak and mostly derived from other cultures. On the other hand, countries like France and India have a strong appreciation of food, including preparation and consumption. Traditional recipes and strong values around food survive over generations. Culture also influences shopping behavior like the amount of food purchased in a single trip, the number of days between shopping trips and the amount of food stored in the household. The amount of food stored has been shown to be directly proportional to wastage.

Socio-demographic factors

Demographic factors like age, family composition and household size, family income tend to have strong relationships with consciousness about food waste. For example, older people tend to be more aware of food waste than younger children, possibly due to exposure to periods of food austerity during calamities, wars, rationing and other emergencies.

Policies

World over policy framework standardizes, regulates and mandates food usage, redistribution and disposal under certain conditions. These policies aim to achieve some overall benefit – food safety or enhanced nutrition. Furthermore, litigation considerations may discourage the reuse or redistribution of edible food. There is a dichotomy at the policy level between the need for food safety and nutrition on one hand over the desire to reduce food waste.

Awareness

Unlike common perception, it was found that most people exhibit a high level of awareness and consciousness regarding food waste, resource and environmental impact and possible role in mitigating hunger. However, they lack knowledge of methods for rationalizing menus and quantities, saving surpluses, and reuse and donation options. Another important outcome was the expressed inability to take any meaningful change steps due to peer and societal pressures.

Customs and behaviors

There is a notable shift in customs related to serving meals at social events like weddings. The traditional custom of Individualized serving of a limited number of food items in a sit-down meal has been largely replaced by lavish buffets, often offering more than 300 items. It is not uncommon to have 4-5 such meals in a single wedding catering to 3,000 to 4,000 guests. It is practically impossible for a single guest to even sample 10% of the service.

Another trend noted was a replication of western ‘course’ meals. Traditionally, Indian meals comprised of a single course where the same plate was utilized for the entire meal. In such a serving, it was easier to mix and match various dishes to suit individual palettes and finish off the meal. In the ‘course’ meal, successive dishes are served separately using individual tableware. Here it is impossible to mix and match. Consequently, the chances of food wastage are higher.

In feasts associated with religious rituals or ‘bhandaras’, several devotees of a shrine pool in resources to organize a community meal. While several individuals are motivated to contribute out of a feeling of religious duty or guilt, frequently only a small percentage actually eat the meal leading to huge food wastages.

In the catering business, heavier and breakable but smaller chinaware plates are being replaced by cheaper and lighter but bigger plastic plates. In its research, Annakshetrea found a positive correlation between the use of bigger and lighter plastic plates and the amount of leftovers.

A correlation was also found between when food was served and the amount of food left uneaten or dumped as leftovers by guests. In instances where food was served late – 10 pm and later, the guests tended to rush, fill up their plates, and consequently, leftovers and scraps were higher.

Possibly people over-estimate their hunger when food is served past usual meal times. This was in contrast to when food was served earlier – around 8 pm when eating was more relaxed and leftovers and scraps were lower in volume. Serving meals earlier perhaps enables people to estimate their hunger more accurately.

Corporate dining and mess halls identified a weekly trend in consumption. Food requirement was reported to go up in the beginning of the week, on Mondays and Tuesdays and tapered off on Fridays. The managers explained this by the fact that many people preferred to work from home on Fridays and possibly the lure of weekend food with family or outings made them less inclined towards food served in the offices.

Another trend noted in India was a replication of western ‘course’ meals. Traditionally, Indian meals comprised of a single course where the same plate was utilized for the entire meal. In the ‘course’ meal, successive dishes are served separately using individual tableware. Consequently, the chances of food wastage are higher.

- © Rajesh - stock.adobe.comLack of standardization

Elsewhere in the paper, the problem of confusion resulting from date labels on packaged food has been highlighted as a cause of food disposal of otherwise consumable food. Due to relatively low use of packaged food, this issue is not prominent, as yet in India, but definitely trend is increasing. In India, the lack of standardization in the food service and FMCG sectors confuses consumers on portion sizes to order. While packaged food industry changes package sizes to suit marketing needs, the restaurant sector has high variability in serving sizes. In such circumstances, customers reported difficulty in ordering and consequent wastages.

Food Waste management approaches

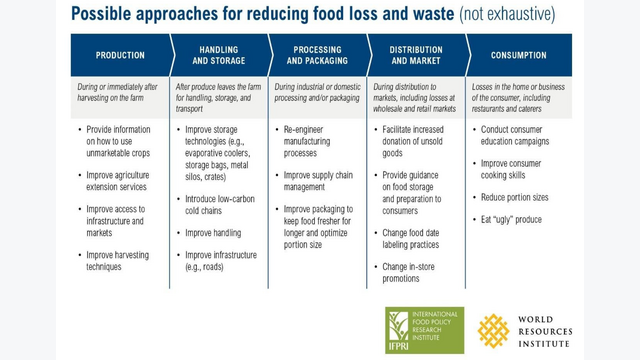

Current thinking on food loss and waste management approaches focus on the themes of reduction, re-use, redistribution, remediation and recovery. These are implemented as a combination of the following strategies.

- Improvements in harvesting, storage and transport of food from farm to fork

- Rationalizing supply chain intermediaries to reduce layers

- Modernizing and expandingthe food processing industry

- Diverting ‘unfit for human consumption food as animal feed

- Resource recovery from dumped food in the form of energy and nutrients

- Consumer awareness and behavioral change

- Rescue and redistribution of food through social and voluntary organizations

- Policy and legislative control

While the top five of the above strategies are well researched and documented as solutions to minimizing food loss, lately there has been considerable interest globally as well as regionally and at individual levels in the last three approaches, particularly in preventing food waste at the consumption level.

Food Waste Prevention Initiatives at the Consumption Stage

Food wastage prevention strategies can be classified into the following categories.

Packaging Innovations

For the past couple of years, scientists have been working on ways to prevent food wastage. A key, and often ignored, facet contributing to the issue of food wastage is lack of optimum packaging material. Packaging helps reduce food wastage by physical protection to prevent damage by

- barrier protection to delay spoilage

- security features to prevent tampering

- properties to promote shelf stability

- more efficient portion control

- marketing that encourages food sales

Researchers from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, US, have, however, taken another step towards solving that problem by developing ‘super slippery’ packaging—it basically enables consumers to squeeze out every last drop of a food product from the package, reducing food wastage, according to a study published this year. “Small amounts of sticky foods like condiments, dairy products, beverages and some meat products that remain trapped in their packaging can add up to big numbers over time even for a single household,” the study notes. The hydrocarbon-based polymers used in the packaging are not only very slippery, but also self-cleaning, the study adds.

Technology Innovations

In addition to scientists, entrepreneurs, too, have invaded the space, developing applications and websites to help restaurants manage their surplus food by making it readily available to those in need. One such initiative has been undertaken by Pune-based Sanjeev Neve, who, in 2016, launched the Food Dosti app, a comprehensive zero-food-wastage platform that brings together eateries, customers, and non-profits. The app provides partner restaurants a platform to ‘publish’ information on the surplus food they have. NGOs and non-profit organisations that have signed up get notifications and can then collect the surplus food, depending on their need. The Food Dosti network has partnered with most restaurants in Pune, its base city, and has now also expanded operations to Mumbai, Neve says. Besides, Food Dosti also rewards customers who visit partner restaurants by giving cashback whenever they finish everything that they order. It also gives customers the option to order partial portions of food to reduce wastage and lets them order the remaining portion free of cost on their next visit to any partner restaurant.

For the past couple of years, scientists have been working on ways to prevent food wastage. A key, and often ignored, facet contributing to the issue of food wastage is lack of optimum packaging material.

Community-based innovations

Minu Pauline, the owner of Kochi-based Pappadavada restaurant, set up a community fridge in 2016, the first in the country, outside the restaurant premises to provide people a medium to donate. Taking the cue, Gurugram-based Rahul Khera, too, installed a refrigerator outside his society last year in Sector 54 with the help of other residents. “After our initiative, nearly five such societies in Delhi-NCR also installed a refrigerator outside their societies,” says Khera, an IT professional.

Volunteer/Good Samaritan Innovations

Many first-generation entrepreneurs are also setting up volunteer-led organisations to transport excess food to places and people in dearth. Delhi-based non-profit Feeding India is one such organisation that began operations in April 2014 to work towards the “cause of hunger and food wastage”. The organisation has partnered with around 3,800 shelter homes across the country where it provides food as an incentive to assist people to get out of the poverty cycle. “We give food to people in shelter homes as an incentive to come to school or a skill development centre… the aim is to not make them dependent on us giving them food… that way, they won’t work… the food is given so that these people get out of the poverty cycle eventually,” says Srishti Jain, co-founder, Feeding India.

Robin Hood Army, a volunteer-based organisation, is another frontrunner in this domain, helping surplus food reach the needy with the help of volunteers whom it calls ‘robins’. While Feeding India is present in 65 cities across the country, Robin Hood Army has its presence in over 80 cities globally. Conceived and conceptualised in 2014 by Neel Ghose, Robin Hood Army has tie-ups with restaurants in cities it is operational in. Ghose was inspired by Portugal’s Re-Food Program which has volunteers collecting surplus food from restaurants and distributing it among the needy. Similarly, the ‘robins’ collect food from the food partners and serve it at shelter homes, basis, to people living under flyovers, outside hospitals, etc. “Our mission is simple: eradicate food wastage and world hunger,” says Aarushi Batra, co-founder of Robin Hood Army.

Another interesting initiative has been taken up by the dabbawallas of Mumbai who are famous the world over for delivering tiffins to around two lakh people daily for the past 125 years. In December 2015, the dabbawallas took up the cause of feeding the needy. Under their ‘Roti Bank’ initiative, the dabbawallas collect surplus and leftover food from weddings, etc, and give it to the hungry and homeless in Mumbai, feeding roughly 150-200 people every day.

Not just community organisations, but hospitality leaders are also working for the cause. From installing water recycling plants to waste converters, they are doing their bit too. In June 2016, ITC Maurya in Delhi set up an on-site waste recycling plant—Bio-Urja—which uses leftover food and minimal water to operate. “Leftover food from the banquet is used in the plant, which is installed on the hotel premises. The gas from it is used in the employee cafeteria as cooking fuel. Soon, it will be a chain-wide initiative,” says Manisha Bhasin, senior executive chef, ITC Maurya, Delhi.

Initiatives at other stages in the Food Chain

It may be useful to look at the food production, distribution, and consumption process and practices to examine options for reducing food loss and waste.

Production

At the farm end, food production covers activities involving harvesting and sorting. During harvest, technology may play a critical role in the efficiency of the harvesting process, as less than-efficient processes may leave a percentage of the crop in the field. Another factor could be the timing of the harvest. A farmer would want to time the harvest with market dynamics. Better information on prices and access to various buying centres would ease decision-making on the timing of the harvest. A certain portion of the harvest would be ‘unmarketable’ due to natural anomalies in shape, colour, size, and other physical deformities of the harvest. This along with crop-residue is typically left in the field, burnt, or used as animal feed on the farm. Mechanisms and markets for such portions may be developed to better utilize them. Options ranging from composting to conversion to fuel and energy for use on the farm can be explored. These could be explored as a collective facility, as small farm sizes may not justify the individual investment.

Handling and Storage

Post-harvest activities involving handling the produce, storage, and logistics comprise the next critical stage of the food production chain. As has been reported earlier, a significant portion of the harvest is lost to inadequate or absent storage facilities. Prioritizing the development of storage facilities and allied transport and communication networks through various agencies is critical. The private sector– especially the food processing industry can play a big role in developing this supply chain element. Indigenous technologies like evaporative coolers, HDPE storage bags, metal silos, and containers can be employed to enhance the shelf-life of perishables like fruit and vegetables. Low-carbon technologies can be explored for the development of efficient cold-chain systems. Skill development in handling and sorting can also lead to a significant reduction in food loss.

Processing and Packaging

In India, there is considerable scope for the development of the food processing and packaging industry to take up market slack, balancing the supply and demand inconsistencies. However, the food processing sector accounts for a significant share of food loss and waste due to heavy mechanization and requirements of standardization. Here, there is a need to re-engineer the production processes to enhance efficiency and create nets to catch process rejects. Stricter legislation can play an effective role in monitoring and control of various processes aimed at reducing, recycling, and reusing. Suitable incentives and economic ‘nudges’ can be created to improve processing, packaging, and labeling to keep food usable for longer and optimize package/portion sizes.

Distribution and retail

At the retail level, legislation aimed at the donation of unsold inventory through social organizations is important. Sharing of suitable infrastructures like storage freezers between retailers /restaurants/hotels and distribution organizations can save duplication of resources and ensure quality in the distribution of such surpluses to the needy. In-store promotions can also be tweaked to create appropriate demand shifts to meet food loss concerns at the retail end. Social media and other apps can be used for disseminating information about availability and prices among consumers to further stimulate demand.

Conclusion

As noted earlier, legislation has very limited scope in preventing food waste at the consumption stage. This is primarily due to cultural and behavioral issues involved. Behavior change at the consumer level can be attempted by creating awareness, avenues, motivations, and rewards through social campaigns like advertising, digital media, work-shops, inclusion in school curricula, entrepreneurship, and facilitation.

It may be noted that legislative control of food loss and waste appears to be effective when targeting upstream supply chain activities like production, storage, transportation, manufacturing, and service sectors. In these areas, legislative control has been shown to have met with effective results, in Japan. At the consumer level, the efficacy of legal provisions appears to be mixed as implementation at the micro-level is difficult for already stretched resources of the local bodies, if tasked with such control. If relatively resource-rich bodies in developed countries are finding it difficult to implement food waste prevention laws, it is certainly going to be difficult in the Indian context. The role of legislation may be more of setting the context and direction rather than regulatory in the strictest sense, it is more descriptive than prescriptive in molding consumer behavior. A larger and more effective role may be played by social and voluntary organizations in awareness creation, driving social change at various levels, and also implementation at the consumption stage. A micro-planning approach to understanding the dynamics of food consumption behavior is essential to make a serious dent in food loss and waste menace.