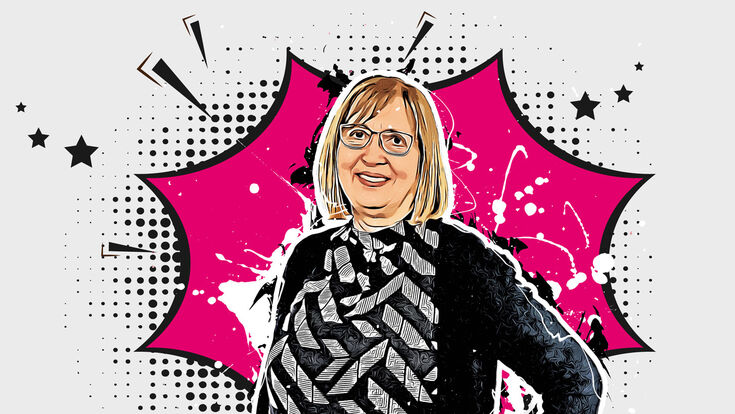

Woman in Waste Management : “Animal by-products are a very valuable raw material!”

“Recycling is the process of collecting and processing materials – that would otherwise be thrown away as trash – and remanufacturing them into new products.” Sounds like a good definition, doesn’t it? In this sense, the rendering of animal by-products is recycling, because the by-products – such as carcasses, feet, heads, feathers, guts from abattoirs or fallen livestock from farms – are collected and turned into valuable raw material for pet food, animal feed production, fertilisers, cosmetics and biodiesel.

Working in the rendering industry is neither glamorous nor prestigious; however, that doesn’t bother Jane Brindle in the least. The 61-year-old qualified microbiologist is Technical Advisor at Leo Group, one of the UK’s specialists in animal by-products and renewable energy, and now also the first female chair of FABRA UK, the Foodchain and Biomass Renewables Association. Her aim is not only to lobby regulators on behalf of the industry, but also to improve the public image of the rendering industry. “It’s generally viewed as a waste disposal process. It’s quite smelly sometimes because of the material we work with, obviously. And it uses a lot of energy,” she says. Many people also have an image of a very old-fashioned industry, thinking of long-ago foot and mouth outbreaks when dead animals were collected and burnt in the fields. But nothing could be further from the truth. The methods are very high-tech and there has been a lot of investment in improving the technology over the last 20 years. And what people tend to forget: we do eat animals, but we don’t eat all parts of them. So, somebody needs to take care of the animal by-products. But Jane Brindle knows there is a long way to go: “People very often don’t know where their food comes from or what happens to it before it ends up on their plate. So, I don’t imagine for a minute they’re going to be thinking about the bits that they don’t eat.”

Fascinated by science

It wasn’t Jane Brindle’s plan to “end up” in the rendering industry. She graduated with a degree in Microbiology and Virology with Environmental Science from the University of Warwick, because she was always interested in science and this was “a new branch of science to expand what I already knew,” as she says. After graduating she started working in a laboratory conducting research on agricultural chemicals. Although the work was interesting at the beginning, the fact that it was regulatory work meant she was doing the same set of experiments on each new compound. Looking for new challenges, she started in the food industry, working in various labs and even setting one up from scratch. “I was presented with an empty portacabin and a catalogue for lab supplies and was told to ‘go for it’,” she remembers, laughing. But she made it work.

Over time, her responsibilities shifted from lab work to the technical management side. In 1993 she started at Woodhead Bros Meat Company, a slaughterhouse and meat packing plant. After a while she was responsible not just for one facility, but for three. “I was never bothered by working where they kill animals,” she says. “I’ve always been interested in that side of the food chain: natural food rather than processed food, so farming and the whole supply chain.”

Subscribe to our magazine or our (free) newsletters!

People very often don’t know where their food comes from or what happens to it before it ends up on their plate. So, I don’t imagine for a minute they’re going to be thinking about the bits that they don’t eat.Jane Brindle

Changing sides

But after Woodhead Bros was bought by Wm Morrison Supermarkets, she was seconded to a project at their head office to implement computer systems in manufacturing. “Which wasn’t really my thing,” Jane admits. So, when she was approached by Danny Sawrij, the CEO of Leo Group, a specialist in animal by-products and renewable energy, to see if she was interested in building up their technical team, she said yes. “I was interested to see what happens to the animal by-products taken away from the abattoir.” Changing sides, so to speak, she gained first-hand knowledge of some of the opinions about the rendering industry: “When I left the meat industry, everybody was saying ‘Oh, she’s going to the dark side’.”

But she never regretted her decision: “I have learnt a lot about the animal by-products industry working at Leo Group and my background in science has helped me to understand the technical challenges facing the industry. My role is now focused on projects, new developments and future business plans and there are always new activities coming along.”

This openness to always try something new also carries over into her private life. After she gave up riding in her late forties – “You have to draw the line somewhere; falling off starts to hurt a lot,” Jane says with a smile – she volunteered to help at shows with the local riding club in order to stay in touch. “When I gave up riding my husband taught me how to fish, which is quite a relaxing pastime,” she says, adding: “As long as we don’t get too competitive over who is catching most.”

Some groups don’t appreciate that we’re actually manufacturing a product. They think we’re just disposing of it and it doesn’t matter what we do with it.Jane Brindle

Valuable work

The rendering industry tries to inform the public about their work. “But I find that sometimes even the regulators don’t really understand what’s happening in rendering and how we get to the end product,” says Jane Brindle. “And some groups don’t appreciate that we’re actually manufacturing a product. They think we’re just disposing of it and it doesn’t matter what we do with it. They treat it as if it’s a waste product that comes out of the abattoir. It’s actually a very valuable raw material that goes into a wide range of finished products.”

Leo Group factories alone process approximately one million tonnes of animal by-products annually. Their plants in the UK, Belgium and South Africa produce about 130,000 tonnes of protein meal and 70 million litres of purified oils every year.

Put simply, rendering is like pressure cooking, Jane says: “We have a huge cooker that’s set to a specific temperature and pressure because the temperature has to kill any likelihood of microorganisms like salmonella and E. coli to make it safe.” The end products are essentially fats and protein meal. The latter can be used as raw material for pet food; a lot of the animal fats are used for cosmetics, animal food, detergent and pet food, but – at least at the moment – mostly for the production of biodiesel.

For fallen livestock, controls are even tighter, but the end products still have a use as alternative fuels, for boilers, cement works, power stations and the fats specifically for biodiesel production.

When she started out in the industry some 12 years ago, Jane Brindle was very often the only woman at meetings. Today, however, there are quite a few women working in the industry, especially on the technical regulatory side. Production, on the other hand, tends to be dominated by men. “It used to be the production people and directors who came to the FABRA meetings; now there are more people doing the actual technical work. Which makes sense too, because most of the problems we face are related to legislation.”

Nevertheless, she had to prove herself initially. “I’ve always been a bit of a quiet person, so I’m not one to take over meetings. But when I do say something, I make sure it’s useful and sensible,” she says. “And I think over the years, because I’ve participated with useful information, people forget about the male-female thing after a while. It’s not whether you’re new or whether you’re a woman, it’s actually what you know and what you can contribute that’s important.”

About Jane Brindle:

Jane Brindle has a degree in Microbiology and Virology with Environmental Science from the University of Warwick. She worked in laboratories conducting research on agricultural chemicals before she started in the food industry. Since 2011 she has worked in the rendering industry as Technical Advisor for the Leo Group. She is the first female chair of FABRA UK (Foodchain and Biomass Renewables Association). Jane lives in Lancashire with her husband.