Guest Commentary Textile Recycling : A textile overflow: The industry must turn off the tap

For those of us who have worked with municipal waste management for decades we did not expect major changes from the new textile waste regulation. Yet, the simple fact that worn-out socks could no longer be disposed of with residual waste caused a stir in Swedish media. Newspapers ran extensive articles, and both radio and television covered the new textile collection scheme.

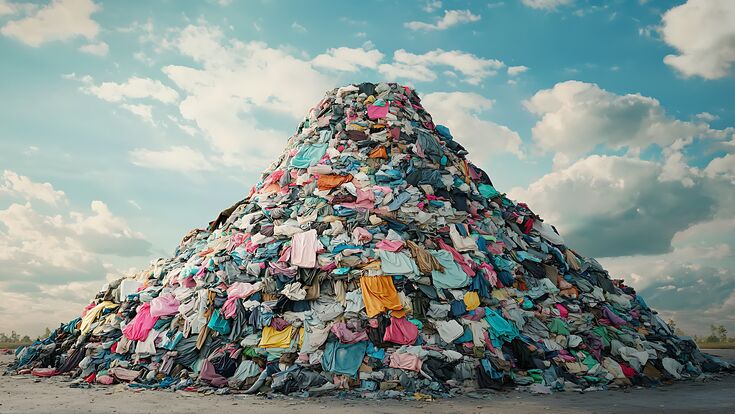

The impact was immediate. Municipal recycling centres reported overflowing containers and struggled to process the sudden influx of discarded textiles. It seemed as if many had been waiting for an opportunity to clear out their wardrobes, wanting their worn-out shirts and stained jumpers to be transformed into new materials through recycling. How did it come to this?

An insatiable market

A key reason is the sheer volume of clothing being purchased. Production and consumption are at record highs. Globally, 100 billion garments are produced every year. Some brands release new collections on a weekly basis. Fashion experts suggest that the clothes already in circulation today could last six generations.

But the driving force is, of course, not necessity. For many, shopping for new clothes is a weekend pastime, and shopping centres are abundant. However, the most significant increase in textile consumption is happening online. Digital platforms bombard consumers with images of attractive, inexpensive clothing that can be ordered with just a few clicks. Sweden is among the countries with the highest rates of e-commerce. Yet, many garments that look promising on screen fail to meet expectations upon arrival, leading to high return rates or immediate disposal. The quality is often so low that it cannot even be processed into new materials.

Chinese fast-fashion giants Shein and Temu have been singled out as particularly problematic. In addition to poor quality, studies indicate that their garments contain hazardous substances.

Several Swedish charitable second-hand organisations refuse to accept clothing from Shein and Temu. Some textile waste collectors have even introduced special containers to prevent hazardous materials from contaminating other textiles or being used as recycled materials in new garments. Recently, the Swedish government announced its intention to remove the duty-free status of such products, which are currently shipped directly to consumers, in an attempt to slow the influx. The EU appears to support this measure.

Low demand for recycled textiles

This is the situation as the EU’s requirement for separate textile waste collection takes effect. The regulation covers clothing, home textiles, bags, and accessories made from textile materials.

The idea is, of course, that textile waste should be recycled into new textiles. Despite its small population – just 2% of the EU – Sweden has invested heavily in textile recycling. The country is home to Circulose, a pioneering industrial-scale facility for chemical textile recycling, as well as Siptex, the world’s first large-scale plant for sorting textile waste.

These facilities have functioned well from a technical standpoint. However, a lack of demand for recycled material has left them dormant. Virgin materials remain cheaper, and few manufacturers are willing to pay a premium for a more sustainable alternative – currently, only 1% of the world´s textiles are made from recycled fibres.

So here we are, with strong public enthusiasm for textile recycling, yet a market for recycled materials that appears non-existent.

>>> Bye bye bye: Europe's problem with used textiles exports

A textile reformation is needed

Out of necessity, the textile and fashion industries face a major transformation. In addition to the vast quantities of garments flooding the global market, the production process itself has a significant environmental impact. The industry must change. What is being produced needs to shift: today’s ultra-fast fashion, with its short-lived collections, must be replaced by more sustainable – and recyclable – products. How the production process works must also be overhauled.

The EU’s upcoming requirement for a mandatory percentage of recycled materials in new textiles could help steer the industry in the right direction. There is also hope that the forthcoming EU-wide extended producer responsibility (EPR) scheme will contribute to this transformation.

Europe must build the capacity to recycle textiles at scale. This is best done by manufacturers who can create materials that are in demand. The entire chain must work in unison – from legislation to production, consumption, and recycling. A larger shift on global level is also required.

Consumers, too, must learn new habits. Interest in second-hand shopping has increased significantly in Sweden in recent years, and fortunately, there are plenty of high-quality garments that can be reused multiple times. However, this has not yet curbed the appetite for buying new items.

More people need to learn how to care for what they already own, wash correctly, repair, and combine garments in new ways. Renting or borrowing clothing for occasional use should become the norm. This way, wardrobes can be refreshed without the world drowning in textile waste.

>>> The world's first automatic large-scale textile sorting plant is in Sweden

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of WMW.

Facts & Figures: Textile waste and production

- The textile industry accounts for 2–8% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- Nearly 100 million tonnes of textiles are produced globally each year, with only about 1% made from recycled fibres.

- Production is often located in low-wage countries, where outdated technology and weak environmental legislation are common.

- Producing 1 kg of new textile:

- Generates between 10 and 40 kg of CO2-equivalents.

- Requires between 7,000 and 29,000 litres of water – often in regions already facing water scarcity.

- Uses between 1.5 and 6.9 kg of chemicals (depending on energy sources, fibre type, and production method).

- Consumption and Waste Flows in Sweden (kg per person per year):

- 13.7 kg of clothing and home textiles are purchased.

- More than 7.5 kg end up in residual waste.

- 3.8 kg are donated to charitable organisations.

- 0.8 kg are bought second-hand.

- The net influx of new textiles per person in Sweden increased by nearly 40% between 2000 and 2021.