Transboundary movement of discarded EEE : Global e-waste flows monitor 2022

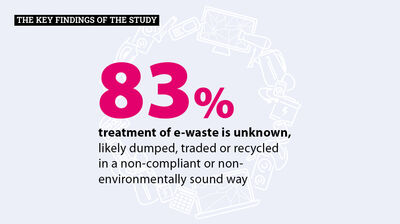

In 2019 53.6 million tonnes (Mt) of e-waste were generated worldwide. That is an average of 7.3 kg per capita. Only 17 per cent of it was managed in an environmentally sound manner, which resulted in $9.4 billion gross value in iron, gold, copper and other valuable materials through recycling.

What happens to the remaining 83 per cent is unknown. These 44.3 Mt might be treated or even recycled in an undocumented way or simply be dumped or burned, with a potential loss of $47.6 billion of raw materials.

We are not done with the numbers. It is estimated that e-waste generation will increase by an average of 2 Mt annually to 74.7 Mt in 2030 and up to 110 Mt in 2050 – unless we change how we handle electric and electronic equipment (EEE). This makes e-waste the fastest growing waste stream globally. Which makes it both a business opportunity – and an environmental and health hazard.

Read more on the topic: "The growing volume of e-waste is quickly overwhelming the current capacity to recycle it"

E-waste is a hazard for health and environment

The mounting volumes of e-waste pose a threat to the environment and public health. In 2021 the World Health Organization (WHO) published its first report on e-waste and child health (Children and Digital Dumpsites). According to the report, workers seeking to recover precious materials such as copper and gold are at risk of exposure to more than 1,000 harmful substances, including lead, mercury, nickel, brominated flame retardants and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Up to 12.9 million women work in the informal waste sector, which exposes them to potentially toxic e-waste and puts them and their unborn children at risk. There are also more than 18 million children and adolescents, many as young as 5 years old, working in the informal industrial sector, of which waste processing is a sub-sector.

Children are very often involved in e-waste recycling as their small hands are more dexterous than those of adults. Other children live, go to school or play near e-waste recycling centres where exposure to high levels of toxic chemicals, mainly lead and mercury, can affect their intellectual abilities.

Like our content? Subscribe to our newsletters!

In the same way the world has rallied to protect the seas and their ecosystems from plastic and microplastic pollution, we need to rally to protect our most valuable resource – the health of our children – from the growing threat of e-waste.WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

Children are particularly sensitive to the toxic chemicals in e-waste because of their smaller size, less developed organs, and rapid growth and development. They tend to absorb more pollutants for their size and are less able to metabolise or eliminate toxic substances from their bodies.

Additional adverse effects on children’s health associated with e-waste include changes in lung function, breathing and respiratory effects, DNA damage, impaired thyroid function and increased risk of some chronic diseases later in life, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease.

“In the same way the world has rallied to protect the seas and their ecosystems from plastic and microplastic pollution, we need to rally to protect our most valuable resource – the health of our children – from the growing threat of e-waste,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General.

From North to South

The international community has called the Global South the graveyard of the Global North’s luxury products. And with good reason. According to some reports, up to 80 per cent of the e-waste generated annually is transported across country borders.

A substantial proportion of e-waste is exported from high-income countries to low- and middle-income countries, where regulations may be lacking or, where they exist, poorly enforced. There is very often a lack of infrastructure, training, and environmental and health safeguards in the places where e-waste is dismantled, recycled or refurbished.

It is difficult to quantify these shipments not only because of illegal waste trafficking but also because there is some sort of grey zone regarding the export of non-functional used electronics for reuse. So even though the impacts in the recipient countries are well known and significant, the real magnitude of this issue remains unclear.

To shed more light on transboundary e-waste flows, the Sustainable Cycles (SCYCLE) Programme – part of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) – has established e-waste monitors. Researchers harvested all possible datasets from the Basel Convention, trade statistics and literature to compile the Global Transboundary E-waste Flows Monitor 2022 (C.P. Baldé, E. D’Angelo, V. Luda, O. Deubzer and R. Kuehr (2022), Global Transboundary E-waste Flows Monitor – 2022, United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), Bonn, Germany). “Such monitoring will require a repeated effort to ensure constant monitoring for improving understanding of the flows, routes, trends, etc. and will ultimately help limit uncontrolled transboundary movements,” Rüdiger Kühr, Head of the UNITAR Bonn Office and Manager of the SCYCLE Programme, wrote in the foreword.

More on waste crime: Waste companies take action to fight waste crime

What is EEE and e-waste?

All electrical and electronic equipment (EEE), as well as its parts that have been discarded by its owner as waste without the intent to reuse it, is regarded as e-waste. E-waste includes a wide range of products, so it needs to be grouped into categories for comparison and international benchmarking:

-

![© blankstock - stock.adobe.com Single chamber refrigerator line icon. Fridge sign. Freezer storage symbol. Quality design element. Editable stroke. Linear style refrigerator icon. Vector]() Category 1: Temperature exchange equipment

Category 1: Temperature exchange equipmentTypically includes equipment such as refrigerators, freezers, air conditioners and heat pumps

-

![© martialred - stock.adobe.com monitor, display, computer, imac, icon, thunderbolt, screen, desktop, laptop, network, isolated, outline, copy, white, view, blank, business, wide, vector, visual, app, internet, tech, portable, digital, black, gray, technology, equipment, flat, modern, illustration, object, front, frame, pc, design, lcd, electronic, keyboard, device, image, border, logo, office, telecommunication, glass, communication, ui]() Category 2: Screens, monitors and equipment containing screens

Category 2: Screens, monitors and equipment containing screensTypical equipment includes televisions, monitors, laptops and tablets

-

![© Janis Abolins - stock.adobe.com shine, website, isolated, electric, white, lamp, innovation, illuminated, power, bulb, glowing, line, sign, vector, symbol, lightbulb, electricity, light, graphic, glow, intelligent, black, idea, flat, icon, energy, illustration, invention, web, solution, think, illumination, background]() Category 3: Lamps

Category 3: LampsProducts such as fluorescent lamps and LED lamps

-

![© nazar12 - stock.adobe.com wash, machine, washing, icon, vector, domestic, house, clothes, appliance, symbol, home, single, laundry, clean, equipment, washer, interior, clothing, clear, room, towel, dry, simple, service, electric, electronic, residential, electrical, household, soap, linen, housework, detergent, app, laundromat, wringer, washhouse, line, isolated, illustration, design]() Category 4: Large equipment

Category 4: Large equipmentWashing machines and dryers, dishwashers, large printing devices and photovoltaic panels

-

![© iz maulana - stock.adobe.com vacuum, cleaner, icon, housework, isolated, design, domestic, house, object, vector, white, equipment, purity, push, contemporary, washer, appliance, cleanup, electrical, element, home, household, illustration, machine, single, logo, cleaning, device, work, image, flat, machinery]() Category 5: Small equipment

Category 5: Small equipmentIncludes vacuum cleaners, microwaves, ventilation equipment, toasters, electric kettles, electric shavers, scales, electric toys, small medical devices and control instruments

-

![© martialred - stock.adobe.com phone, ringing, icon, iphone, smartphone, 14, mobile, vibrating, ring, vibration, x, app, call, center, clip art, clipart, communication, contact, device, electronic, flat, incoming, internet, isolated, line, message, modern, notification, notify, phonecall, ringer, robocall, sales, screen, service, sign, signal, silhouette, smart, sound, support, talk, vector, vibrate, voip, website, notch, shake, shaking]() Category 6: Small IT and telecommunication equipment

Category 6: Small IT and telecommunication equipmentTypical equipment includes mobile phones, personal computers, printers, game consoles, calculators and other small IT equipment

The key findings of the study

- An estimated 5.1 Mt of e-waste (almost 10 per cent of total global e-waste) were transported across borders.

- 1.8 Mt of the transboundary movement are shipped in a controlled manner, meaning it is reported as hazardous waste according to the Basel Convention or it is exported as highly valued separated printed circuit boards to a specialised end processor.

- 3.3 Mt of the transboundary movement are uncontrolled as used EEE or e-waste. This ranges from entirely legal trade like used EEE for reuse in recipient countries to illegal e-waste trafficking to countries with lower treatment costs. Movement is commonly from high-income to middle- and low-income countries, further trickling down regionally towards the poorest within the region. This movement happens at both continental and intraregional level.

- Only 2 to 17 kt of e-waste are seized as illegally traded from the EU, which in all likelihood is just the tip of the iceberg in regard to the megatonnes of uncontrolled shipments. This shows just how limited the inspection capacities are.

- Of the 1.8 Mt of controlled e-waste transports, 1.5 Mt were hazardous waste shipped under the Basel Convention. Compliance with existing national and international e-waste legislation is the driving factor. High-income countries have the right infrastructure for e-waste management, which is why they import the majority of controlled shipments.

- 0.36 Mt of printed circuit board waste is primarily imported to East Asia, Western Europe, North America and Northern Europe, where specialist recyclers are located. Despite being a high-value component of e-waste (it contains the highest concentration of platinum group metals), only 0.4 Mt of the global printed circuit board waste is separated from e-waste and recycled in specialised facilities.

- The primary driving factors for illegal e-waste trade:

- Exporting is often less expensive than managing the waste domestically

- The presence of developed markets for raw materials or recycling facilities

- The location of EEE manufacturers

Regarding the continents and regions, the study found out the following

- Europe, East Asia and North America have the capacity to manage hazardous waste and printed circuit board waste. However, the recycling capacity for printed circuit board waste is approximately 0.5 Mt, which is far from enough to manage the 1.2 Mt embedded in e-waste. Hazardous e-waste recycling capacity is not known, but given the incomplete collection and recycling rates for e-waste in these regions, it is clear that not all e-waste ends up in these facilities, despite the existence of recycling infrastructure.

- Europe, East Asia and North America are the main exporters of uncontrolled used EEE and e-waste, mainly to Africa, South-East Asia, Central America and South America.

- Recipient countries in Africa, South-East Asia, Central America and South America have low recycling rates and a high number of informal workers. The major import hubs for uncontrolled exports of used EEE and e-waste are North Africa and West Africa, mainly from Europe and to a smaller extent from West Asia. This is placing a huge burden on the environment and informal workers. For example, Africa exports 13 per cent of its printed circuit board waste to Western Europe, with a high risk of cherry picking that leaves the hazardous components unregulated.

- Eastern Europe receives imports of uncontrolled used EEE or e-waste exports from other European countries.

- Southern Asia shows little transboundary movement. It is assumed that it has a strong, informal local market for managing e-waste.

- West Asia is an import and export centre for both controlled and uncontrolled transboundary movement of e-waste.

- Central Asia and the Caribbean do not track controlled movements of hazardous waste, but import significant volumes of uncontrolled used EEE and e-waste, posing a risk of unsustainable management.

- Oceania’s reporting on e-waste imports and exports is limited, but New Zealand and Australia mainly export generated e-waste to Asia.

The main reasons for the increasing amount of unmanaged e-waste:

- Rapidly increasing volumes of e-waste

- Absence of specific e-waste legislation: only 78 of the 193 UN Member States have a policy, legislation or regulation in place

- Limitations of e-waste management infrastructure

- Competition between formal and informal sectors for the valuable parts of e-waste: the latter plays a key role in the collection and recycling of e-waste in low- and middle-income countries.

- Legal and illegal import and export issues: while the shipping of e-waste is only regulated for hazardous waste by both national and international legislation, the uncontrolled trade of e-waste – often mixed with used EEE – can favour corporate or organised crime.

- E-waste was among the top three waste categories illicitly traded between 2018 and 2020. It was mainly undeclared or falsely declared as used EEE, household goods or another type of waste.

- Mixing of e-waste with other waste streams such as scrap metal: although high-income countries have the appropriate recycling infrastructure, a large part is still being managed outside compliant recycling sectors. Part of the e-waste is exported for reuse or is recycled with metal scrap.

Good to know

An interesting fact is reported by both the enforcement sector and the academic community: the most common method for the illegal disposal of e-waste is to export it together with legal shipments – specifically second-hand and end-of-life vehicles. West and North Africa are the top receiving regions, where 62.5 kt and 47.8 kt respectively of e-waste and used EEE charged on used vehicles end up. The top exporters are Western Europe (113 kt), Northern Europe (30.4 kt), and North America (30.3 kt).