Composting : Bioplastics and Composting: Not a Love Match

In an effort to be greener, the plastics industry is increasingly relying on the production of bioplastics. According to European Bioplastics, the association representing the interests of the bioplastics industry in Europe, global bioplastics production capacities are set to increase from around 2.23 million tonnes in 2022 to approximately 6.3 million tonnes in 2027. Still, bioplastics currently represent less than 1 per cent of the more than 390 million tonnes of plastic produced annually.

For every conventional plastic, there is already a bioplastic alternative available on the market that has the same properties: from agriculture and horticulture (think mulching films) to the automotive industry and consumer goods and electronics, from coating and adhesives to food services and packaging, bioplastic is everywhere.

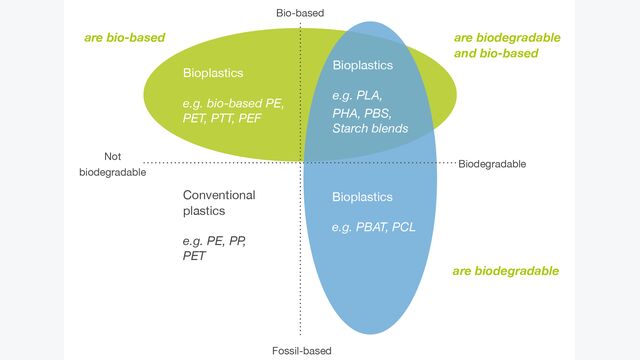

But not all bioplastics are the same. Despite it being the material du jour – promoted as an alternative to conventional petroleum-based non-biodegradable plastics – bioplastic is still ill defined.

What is bioplastic?

The term is used to describe both plastics that are ‘biobased’ or made entirely or partly from naturally renewable materials, and ‘biodegradable’ or able to be broken down by microbes, as Emily McGill, Program Director of the Compostable Field Testing Program (CFTP), an international non-profit research platform to bring field testing to composters across North America and beyond (see interview), explains. “This can cause quite a lot of confusion. Not all bioplastics are biobased, and not all bioplastics are biodegradable.”

It gets even more complicated when we look at the compostability of a product: “Seeing something called a ‘bioplastic’ is not enough to determine whether it’s compostable or not,” McGill says. “If a bioplastic is labelled as ‘biodegradable’, this is still not enough information, because the term ‘biodegradable’ does not indicate whether that item can be composted. In order to figure out if a biodegradable plastic is suitable for composting, it’s critical to assess whether it has been tested according to a broadly accepted third-party compostability certification, and also whether that item is accepted in a given area’s composting system.”

Want regular industry updates? Subscribe to our newsletters!

Lab-scale test vs. real-world composting

In North America, both the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and the Bureau de Normalisation du Québec (BNQ) have created testing standards to determine the biodegradability of a product. These standards also draw on the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Certification agencies have then taken these standards to create a more precise definition of compostability with added criteria around ingredients (e.g. no added PFAS) and non-toxicity through germination testing, as McGill, who is also Manager of Research and Communications for BSIbio Packaging Solutions, further explains.

The situation in Europe is very similar. There are various seals and standards that certify compostability. The best-known standard in Europe is EN 13432, which has been valid for all member states of the European Union since March 2001.

“In this process, 90 per cent of the bioplastic should break down into particles that are smaller than 2 millimetres,” explains Ulli Volk, Deputy Head of Waste Management and Material Flow Management at Vienna waste management MA 48. “Since these tests are carried out under optimised conditions in the laboratory, not every plastic certified as ‘biodegradable’ is also ‘compostable’. According to ÖNORM EN 14045, the compostability of packaging can be tested under realistic composting conditions or under defined conditions in a pilot plant.”

The problem with the existing standards is that they prescribe lab-scale tests which do not correlate to real-world composting conditions.

Regardless of their certificate, bioplastics are not desirable in composting.Ulli Volk, Vienna waste management

Bioplastic is a contaminant

As a result, bioplastics are classified as contaminants and are removed from the waste stream in the composting facilities. “Because of the difficulty of identification of compostable products vs. lookalikes, there is an increase in the cost of removing non-compostables from the incoming food scrap stream,” says Diane Hazard, Executive Director of the Compost Research and Education Foundation (CREF). “Most facilities use hand labour to remove these contaminants. Removal before or during processing, or at the finished product, also adds more cost in the overall management of contaminates. Education, and inspection at the point source of generation, is key to keep contaminants out of the food scrap stream.”

Ulli Volk agrees: “Bioplastics cannot be distinguished from conventional plastics in the rotting material and often have to be sorted out manually. At the Vienna composting plant, the majority of plastics are separated before composting in the course of mechanical processing or separation of impurities.” Furthermore, bioplastics do not add any value to composting and do not contribute to humus build-up. Unlike biogenic waste, bioplastics contain no nutrients and are worthless for both the composting process and the end product, compost, as an expert paper by the Austrian Water and Waste Management Association states. “Regardless of their certificate, bioplastics are not desirable in composting,” Volk says.

Oliver Buchholz from European Bioplastics responds: “Currently, there is very little data that support these allegations concerning the performance of compostable plastics in industrial composting facilities. The technical standards in the EU composting landscape alone are already very different. Some facilities are very old and in no way respond to the current requirements of a modern recycling system.” (see full interview)

Nevertheless, 2018 Environmental Action Germany (Deutsche Umwelthilfe e.V. – DUH) published a study conducted among about 1,000 German composters. The result: the majority see bioplastics as contaminants that need to be removed and thus cause higher costs.

There is more and more research on the compostability of bioplastics. In 2018 scientists at the University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences (BOKU) in Vienna assessed the impact of biowaste collection aids made of ‘biodegradable materials’ on composting plant operation (link in German). According to the Austrian waste regulation, these biowaste collection aids – commonly known as organic waste bags – might be used to collect biowaste, but they should not end up in the organic waste bin. Yet they are advertised as compostable biowaste bags and sold as such. The researchers found microplastic particles in all samples, although the variation from sample to sample can be of different levels. So, not all certified plastic bags can be broken down in the course of composting. In principle, it can be assumed that the remaining plastic fragments can also degrade completely after composting. However, it is not possible to assess how long this degradation will take.

Biodegradable doesn’t equal compostable

Apart from the fact that compostable bioplastics, often used for organic waste bags, single-use cutlery, food trays etc., too often do not in fact decompose in a composting facility, there is much confusion among the public about the terms compostable and biodegradable. “For consumers it’s mostly the same thing,” says Marieke Hoffmann, Senior Expert Circular Economy at Environmental Action Germany. “But from a technical point of view, there is a big difference: degradability refers to the property that microorganisms can biologically utilise the material.”

Emily McGill elaborates: “Speaking very broadly, a product identified as compostable will ideally break down in the same or a similar time frame to totally natural organic materials, and result in no negative effects on the resulting compost (i.e. be non-toxic). This breakdown needs to involve biodegradation – the actual molecular transformation by microbial activity of a material – not just disintegration.”

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletters!

Biodegradable is a sham. The word should be banned from use. Everything is biodegradable over time. Nuclear waste is biodegradable over thousands of years.Frank Franciosi, USCC

For Frank Franciosi, Executive Director of the US Composting Council (USCC), the term biodegradable is extremely problematic: “Biodegradable is a sham,” he says. “The word should be banned from use. Everything is biodegradable over time. Nuclear waste is biodegradable over thousands of years. ‘Compostable’ should not be used interchangeably with biodegradable. Almost all organic material is compostable. If it was derived from plant or protein it will compost.”

So even though even compostable bioplastics are not allowed in most composting facilities – in Germany, for example, packaging waste must not be put in the biowaste bin, regardless of its origin or material – more and more ends up in the biowaste stream. “We did a representative survey asking how people would dispose of packaging that says compostable. Half of them named the organic waste bin,” says Marieke Hoffmann.

Bioplastics for a clear conscience?

Better labelling on products and on waste bins is a way to improve source separation – and educate people. According to Franciosi, a harmonised labelling system might help to improve composting rates while at the same time reducing the amount of unsuitable material in the biowaste stream. The USCC is currently working with BPI to establish a model standard labelling and identification protocol.

He sees a possible future for bioplastics if they can be easily labelled and identified. “Other like products cannot use the same colour, name, label and identification,” Franciosi says, adding: “Uniform colour would go a long way if all governments would adopt a standard policy and fine any companies that produce lookalike products. They also need to bring in food waste. Not all food packaging products are suitable to do this. Those products should be made reusable or recyclable.”

The latter is theoretically true for bioplastics at the moment. But as the Austrian expert paper states: “In the public discussion, reference is often made to the fact that material recycling is also possible for biobased plastics. This is theoretically correct, but in practice it is currently not organisationally or economically feasible due to the lack of separation of the different types of plastics by type.”

Environmental organisations such as Environmental Action Germany see an even bigger problem: bioplastics do not contribute to reducing the amount of waste. Very often the material is used for single-use products where more sustainable alternatives exist. “Currently, bioplastics are mainly used as a marketing tool to present products in a more ecological way,” Hoffmann says. “They are more expensive than conventional plastics. So that is given as the reason for their use.” Products are advertised as being ‘compostable’ and ‘plastic-free’, allowing ‘indulgence with a clear conscience’, as a recent product check by Environmental Action Germany shows. So, the image of products that are generally seen as non-environmentally friendly, such as coffee capsules, single-use cutlery and takeaway tableware, is improved and they can be used with a clear conscience.

But life-cycle assessments show that, overall, bioplastics are often just as harmful to the environment as conventional plastics, says Marieke Hoffmann: “Of course, there is less need for fossil raw materials, but production pollutes water, soil and the climate just as much, and the cultivation of plant raw materials competes with food production. Mostly sugar cane and maize are used as raw materials, which are grown in large monocultures in conventional agriculture, for example in Brazil.”

"This feedstock is currently the most efficient to produce bioplastics, as it requires the least amount of land to grow and produces the highest yields” says Oliver Buchholz. “But the bioplastics industry is also researching the use of non-food crops, such as wood, waste materials, and CO2 with a view to its further use to produce bioplastics materials.” Furthermore, he says, the area required to grow sufficient feedstock for today’s bioplastics production just reaches a little bit more than 0.01 percent (0.8 million ha) of the

global agricultural area of 5 billion hectares.

Bioplastic Composting Trial

How well do products advertised as compostable decompose?

In autumn 2022, Deutsche Umwelthilfe (DUH, Environmental Action Germany) conducted a rotting trial at the RSAG Swisttal composting plant with a number of products advertised as compostable or biodegradable. Some of the products were certified as compostable, for example according to DIN EN 13432.

The results showed that most of the packaging and products had hardly changed as a result of the rotting process.

Bioplastic is still plastic

One fact that should not be forgotten is that bioplastic is still plastic. It is specially made to have the same properties as conventional plastic. Which also means that very often the same additives are used in its production.

In 2020 a research group at the Institute for Social-Ecological Research (Institut für sozial-ökologische Forschung, ISOE) and Goethe University Frankfurt published a study on the in vitro toxicity and chemical composition of bioplastics, looking for an answer to the question of whether bioplastics and plant-based materials are safer than conventional plastics. According to the scientists, you have to look at the material at the chemical level in order to understand the impact of bioplastics on health and the environment. What they found out is rather sobering.

According to the study:

- Most bioplastics and plant-based materials (67 per cent) contain toxic chemicals.

- Cellulose and starch-based products induce the strongest in vitro toxicity.

- The material type does not predict toxicity or chemical composition.

- Biobased/biodegradable materials and conventional plastics are similarly toxic.

According to the authors of the study, a “comparison with conventional plastics indicates that bioplastics and plant-based materials are similarly toxic. This highlights the need to focus more on aspects of chemical safety when designing truly ‘better’ plastic alternatives.”